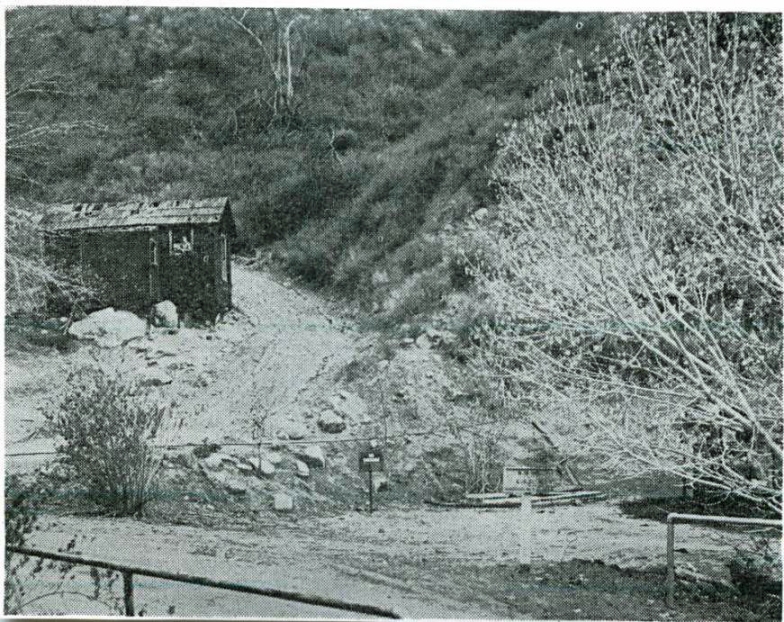

By 1880, the eastern boundary of production could probably be guessed, so down the canyon, below the faulting, the cabins, and housing, for families started building. First they were considerably spread out for a mile on the slopes and creek banks. It was not until 1888 that the second superintendent’s house, still standing by the gate, was built.

As long as Newhall had the Southern Hotel, entertaining stock prospects were simple. When the hotel burned in 1887, that ended that. True, down by the Newhall depot, the old California Star Oil Works Company had built the “Newhall cottage,” occupied by Christopher Leaming, staffed by a Chinese, and was the “downtown” office of a budding industry, but it wasn’t adequate for entertaining.

By 1885, the true course of nature made necessary school facilities. Senator Felton was the money man of Scofield’s project, so a school district was formed named “Felton.” A school was built which still stands a hundred yards or so from the big house at Mentryville. Until 1932, it was in use.

As a matter of fact, in 1927, there were 18 students in this school. By 1932, only Phil Sitzman represented the sixth grade. Barbara Sitzman (Mrs. Paul Cook) and Lois Cheney (Mrs. Henry de Moss) were the fifth grade. Nicolene Cheney (Mrs. Wayne Graham) was the third grade. Bernice Brombacher was the school teacher. The next year, the school district was absorbed by Newhall district.

Pico was a “Company town.” There were no stores. Morning and afternoon, the stage made a round trip to Newhall for shopping and passengers. Liquor was taboo in the camp. This may have been reflected in the prosperity of the Stage driver. Leighton’s homestead was just over the camp lines, which was sometimes thought to be a convenient setting for recreation, being only an easy walking distance.

Leighton may or may not have built the “Derrick” saloon, in Newhall, down on Eighth St. fronting the square. At one time or another, he may have had something to do with the functioning of a supply line. Cochems had a little bakery in Pico. Incidentally, a dance hall was built by the Company by the side of the school house. Pico dances were welcomed, as a change of pace by the folks down at Newhall – if they were lucky enough to get an invitation.

For years, Chester Johnson would gather his trio or quartette and the ladies would provide refreshments. All joined in the dance. The school house originally was used for the dances but too many people showed up and the Company put up another building along side for recreation only. Before Chester’s day, it may be correctly assumed there was some kind of Music in the Air.

You can’t reconstruct things of the past without encountering some of the darndest problems. For example – the wells Scofield drilled in the late ‘70s for the California Star Oil Works Co., were numbered CSO – most logical. Then the PCO came into being in 1879 – and all the wells were changed to PCO’s. Some folks used to say that the south side of the canyon was CSO, and on the north side it was PCO. That’s what they said.

One thing is positive. Rome sat on seven hills. Pico occupied only three hills. Pico’s derricks roamed freely over the CSO hill, the PCO hill, and would have roamed over Christian Hill only the wells there drilled by Hardison & Stewart had been dusty. (Lyman Stewart is said to have detested profanity, and the facts of life as regaled entertainingly by his employees on his derrick floors, hence the name, Christian Hill.)

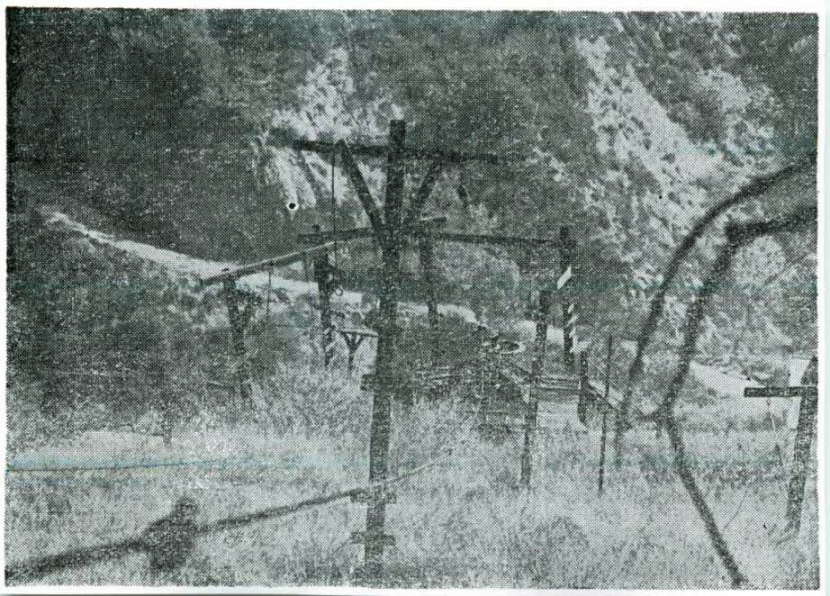

Some of the old well sites are still designated by little white signs. Trouble is, no pattern of nomenclature is apparent. In 1906, a tremendous fire burned across those hills, and the derricks went up in flames. Some of the derricks, but not all, were replaced.

Which is the CSO Hill? Is it back, north, of No. 4. Or could it be the PCO hill? Eighty years is a long time for a landmark to hold its identity. There is a picture in existence labeled “PCO Hill – 1893.”

Mrs. Mable Taylor states that she used to go up to Pico for the dances, and to visit here Pico friends, from the middle 1880’s to the end of the century, and the CSO hill is north of the road. Howard Goldberg started work in Pico in 1903 and for years lived in the bunk house, with the aid of the boarding house. He said Mrs. Taylor was positulutely right. Mrs. Cook (Barbara Sitzman), lived in Pico, 1927-1937. She always understood the CSO was on the north. For that matter, so spoke Col. Philip Sitzman, on his recent visit to boyhood scenes. The PCO jackplant is on the south. The SCO jackplant is on the north.

Architecturally speaking, Pico’s buildings were somewhat austere. They lacked romance, aesthetics, and maybe beauty. The heart of the complex was the machine shop. It could handle any mechanical breakdown … or there was a change of shop foreman.

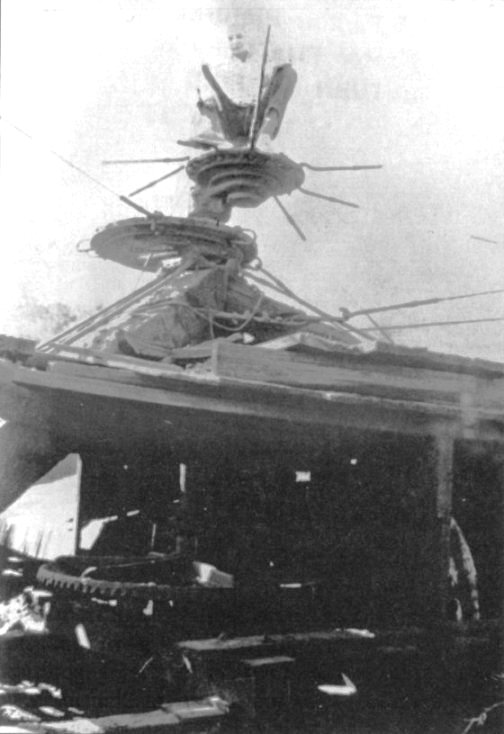

Spring pole drilling was succeeded by steam. Old fire box boilers, or the remnants of same, are still to be found in most unexpected places.

It was a long, far call to the mills of Pennsylvania. Here you really were the Captain of your Soul. Twist offs in the small diameter wells could and did happen. That would be the driller’s hard luck. Sometimes a soap block dropped down the hold would give the impression of just what had gone wrong. If it didn’t, you just tried everything first with homemade spears, blocks, traps, etc.

Forty years ago, the loading platform, by the shop, was covered with such tools. Later generations of oil men never did figure out what some of the oddities were designed for.

How many folks actually lived in the Pico? Payrolls back in 1887-88-89 vary from 12 to 37. However, no one has found a PCO Timebook of the period hereabout, and a PCO timebook would also have to be considered.

About 1908, Goldberg thinks there were over 100 employed, as there was a lot of road work being carried on. It must have been roads, for records do no indicate more than normal drilling activity.

There were surprisingly few Californian names in the Time Book, but many of the importations from the Pennsylvania “stuck.” Names familiar to this generation of Valley folks would include Suracco, Tychsen, Quigley, Mayhue, Cochem, Whitney, Galbraith, Russell, Young, Chaiz, Cheney, Johnson, Sitzman, Barton, Dill, Mentry, Biscailuz, McDermott, Ross, Emmons, Wooldridge, Reynolds, Huddlestun, Pinkston, Goldberg, Arey.

Probably in excess of 22 families lived in Pico, through the first decade of this century, bachelors not necessarily counted. It took five children to qualify a school. Not until about 1920 were children in short supply. The school had opened in 1885. The shortage was successfully plugged by Morris Dill, who was tired of the tides and freezes of the Bay of Fundy, and landed in Newhall with nine children. That covered the school problem adequately for Superintendent Walton Young who practically reached for Dill’s job application. Until Dill’s transfer to the field at Chowchilla, about 1932, the school was saved.

Pico’s first superintendent was Alec Mentry. He was succeeded by Walton Young, at the turn of the century, who had started the Pico machine shop years before. Young retired in the late twenties. Charles Sitzman was transferred to Pico to fill the vacancy.

Actually, the decline of Pico probably started just after Mentry’s passing. Little drilling was carried on. Employees were shifted to other fields. Pico could never by competitive with, for example, Taft or the San Joaquin oil fields. As the payroll shrunk, it seemed to be a prerogative of the old timers to pick up their cabins and move. Newhall still has some of those little homes, slightly outmoded, maybe, but still in use.

To Walton Young, Pico was probably just his job. He spent his working life in the canyon. To his successor, Charles Sitzman, Pico was a chunk of California’s history. Many a specimen of early oil fields equipment, he hauled down to the “Works,” in hope of intelligent preservation in native background of primitive petroleum production aids. As a matter of fact, much of the display in the Union Oil Co. Museum at Santa Paula was borrowed from the Pico oil fields.

In spite of its isolation, which was plentiful, Pico was a child’s paradise. There were so many beautiful hills and canyons to explore.

Col. Philip Sitzman, USA (ret.) was up in the Pico lately for the first time since 1937. For audience, he had his wife, four children, his sister, and a nephew. As reminiscences flowed, a cross section of childhood life in the old camp emerged.

Down this canyon, on beyond the PCO hill, lived the bob cats – heavens knows how many. Up from Newhall would come Jiggs Ullum, bringing his dogs. The cats would be caught alive for a ready market. The mountain lions, also to be found roundabout, took a different type of treatment, more of a lead poisoning pattern.

On another hill, under the sheer face of a waterfall, was a favorite camping spot. It was so darned difficult scaling those hills, that it took an overnight hunt to make is work while. In another canyon, Phil remembered getting his first deer.

Local children made their spending money off calves. Grazing didn’t cost anything and it helped towards fire protection. There was lighter hunting available for rabbits and squirrels. Anyone could have a horse, or even a cow, and of course chickens. As you grew older, entered high school, any of your new school friends loved to come visiting in the canyon. One was always busy doing one thing or another. It gave a change of pace.

Up in Tank canyon, or 14 canyon, (depending upon your generation) were caves in the sedimentary formations. Bat Cave went back into the hill quite a little. Cave prospecting is usually fun.

To Nicolene Cheney, (Mrs. Graham) childhood in the old camp meant roaming the hills, and picking the native flowers. She was somewhat impressed by the rattlesnake she didn’t pick because she decided to go home hurriedly, then and there.

The Pico creek was dammed by the children and it made a wonderful wading pool for summer time.

And of course, the Company did put in a tennis court.

Then, too, have you ever lived in a slightly isolated camp where the outside contact came via stage?

If you have, maybe you can remember the thrill every time the Stagecoach rolled in. Sure, it was vicarious possible – meaning that you couldn’t exactly explain the why fore. That would be just another kick living in a mining camp.

Possibly the nearest approach to Sitzman’s ideas came some years too late. There weren’t any houses left in the Pico, outside of the old Superintendent’s house. In fact, nothing could be damaged very much.

At the mouth of Tank, or No. 14 canyon was a little flat place where Grandpa Emmons dug in a small garden. The name Emmons must have been on the payrolls a couple of generations. Seniority always counts, maybe that’s why the garden. Morris Dill had a garden too, many years later, but he was on the slope outside the boundary fence.

Grandpa ultimately passed on. His garden got slightly altered, and is now labeled “Johnson Park.” Who Johnson was, no one seems to know – except perhaps the top brass at San Francisco.

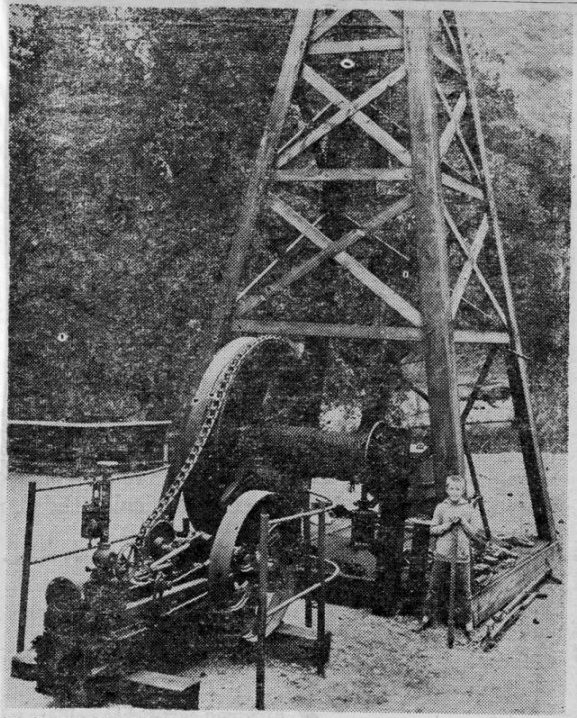

Anyway, there’s a little derrick around 22 feet high. It’s equipped with one of the many old steam engines around the place and all hooked up ready to run. It’s even labeled – “Cochems No. 1”. (Everybody knew Cochems – one or more of them.) It’s a period piece. The Park is used for employee’s picnics – or groups of Petroleum Pioneers in a playtime mood.

Regardless of what you say, there couldn’t possibly be as much fun at Johnson Park as there was in the days of the little dance hall next to the Felton school.

It’s sort of quiet in the Pico these days. Manzers live in the old Superintendent’s house. They love the solitude and beauty of the canyon. So does Alice, although she does have to come down to Hart High every day. Darryl is at Peachland school. Outside of school hours, they do just what they would have done 50 years age, hike, ride, chase cows, etc. and et al.

There’s a Standard pumper who comes over from Martinez canyon every day. Some of the old wells are still strippers. The jackplants aren’t going – they haven’t for many years. Of course, practically all the buildings are gone. What man failed to destroy, Pico creek attended to.

It’s through the gate for the last time. Acknowledgments are in order to Mrs. Paul Cook for much photography and help in reconciling old and new names of landmarks, as well as for memories from her Pico childhood. Mr. Richard Trueblood cooperated with some beautiful photography. Mr. Howard Goldberg and Mr. I. C. Gorden again helped with identifications and stories of the past. Mrs. Mabel Taylor, as usual, contributed to the whole effort.