Lang – The Sterling Borax Company by Ruth Cornwall Woodman

Mrs. Ruth Woodman at Sterling Borax Mine site in 1947. Photo credit - The Borax Collection - lan03a - Death Valley National Park - The National Park Service.

Introduction

The following chapter was part of the research done by Ruth Woodman in the years 1947-1951, for her book “Story of the Pacific Coast Borax Company” (L.A., Ward Ritchie, 1951, 58p). It was not used because of restrictions on the length of the book, so this is probably only a draft. This was found in the Ruth Cornwall Woodman Papers, University of Oregon Libraries, Special Collections and University Archives.

Ruth Cornwall Woodman was born on November 26, 1894, in New York and died on April 2, 1970, in Los Angeles. She was the mother of two and married to a New York investment banker. She was a graduate of Vassar College. While working as a copywriter at the H. K. McCann advertising agency, Ruth was asked to create a radio show sponsored by her employer’s client, the Pacific Coast Borax Company. She thought that the show should be tied to the sponsor, who agreed, but wanted her to travel to the region so that she could create real stories. While there, she was often accompanied by William Washington “Wash” Cahill, a long-time employee of the Pacific Coast Borax Company and a player in the following Sterling Borax story. Cahill would introduce her to many old timers still living in the region. Ruth Woodman became one of the foremost authorities on Death Valley history and folklore. Her radio show became “Death Valley Days”, running on radio from September 30, 1930, through September 14, 1951. Then it was on TV from 1952 to 1970, nearly 20 years.

The handwriting in the document was not very good and the style of many of the individual letters were not the same as they are today, making converting some of the words into text very difficult. If I could not figure out what the word was, then I replaced it with [????]. I did not intentionally change any of the words, but I may have made a mistake in converting a few of them. The photos were all added by me. There were no photos in the original manuscript.

Chapter XII

Lang – The Sterling Borax Company

By Ruth Cornwall Woodman

|

| Francis Smith |

Smith’s(1) annual reports to London had a certain informal quality about them. Like family letters, they not only recounted all the household news, but included bits about the neighbors as well.

“Blumenberg(2) has six men working on a claim near Daggett.” “The Calm Brothers(3) shipped a few tons of ore from their mine in Ventura County.” “Thorkildsen(4) is doing a little work near the Stevens Group(5).” The president of P.C.B. Co.(1) kept a watchful eye on all of them. There was little, if anything, to report with the war of competitive activity during the first half of 1907. Down in the Daggett region the American Borax Co. had abandoned its mine and removed its machinery. The Western Mineral Co. had also discontinued operations. In the Frazier ore district(6), Stauffer closed down in April and the Calm Brothers were later to follow suit. As the fiscal year approached its close, the Lila C(7) was the one borate mine of any importance in operation in the West.

Then, like a bolt in the blue, around the middle of August came the news of the discovery at Lang. It reached the P.C.B. Co. in the form of a letter to Wash Cahill(8) from Jack Duane.(9) Duane was agent for the commission house of D. W. Earle & Co. with an office in the railroad depot at Daggett. He forwarded freight to the T and T(10), and he passed along mining information he picked up from time to time. This tip was a really hot one!

A bag of ore samples had arrived at Daggett. It was addressed to Henry Blumenberg(2) of the American Borax Company - express collect. The sender was a man named Ebbinger.(11) The postmark was Lang, California. Mr. Blumenberg was only mildly interested – not enough to want to pay the charge. Like all borax operators he was always receiving samples of ore, most of these worthless. Lang was only a short distance from Los Angeles, hardly beyond the city lights. There was no borax around there. For days the sack lay there in the Daggett depot, unopened. Finally, Blumenberg’s curiosity got the better of him. Reluctantly he forked up the two dollars due and dumped the samples out on Duane’s counter. Both men let out whistles when they saw the glistening white crystals. Here was high grade colemanite. It didn’t take an assayer to tell them that. And Blumenberg had let four whole days go by! How many others had received similar samples were representatives of rival borax companies already at Lang?

Blumenberg hopped the next train west, prayerfully, and Duane promptly dispatched a letter in the opposite direction to Wash Cahill in Ludlow. A wire would have been quicker, but were liable to interception. Cahill shoved the letter to John Ryan(12), who told him to go to Lang at once and report back. Cahill took the midnight train out of Ludlow. The first person he bumped into when he stepped off at Los Angeles the next morning was Henry Blumenberg. Cahill murmured something about coming in from the desert to see his family and hurried out for the station, leaving Blumenberg staring suspiciously after him. There was no train up to Lang until evening. The conductor looked surprised when Cahill handed him his ticket. Was he sure he wanted to go to Lang, nobody ever went there. Nothing there but the depot.

|

| Henry Blumenberg |

It was almost midnight when Cahill got off the train at Lang and introduced himself at the operator on duty as coming from the T and T Railroad(10). He had heard of a borax mine being found nearby. The man nodded. “Up Tick Canyon – five, six miles from here.” “How can I get there?” Cahill wanted to know. “Same way the other feller did” suggested the operator. “Feller who was here yesterday. By team.” Cahill knew even before the operator described him that the other man was Blumenberg. He sat all night in the railroad depot feeling chilly in spite of the fact that it was mid-August. At 7 a.m. the station agent appeared and Cahill made arrangements with him to be taken to the mine. The agent borrowed a spring wagon and a pair of horses from a farmer up the canyon and drove Cahill over the same ground he had driven Henry Blumenberg 24 hours earlier. On the way he told Cahill the story of the discovery.

It had been made by two prospectors, Henry Sheppard(13) and Louis Ebbinger(10), who had a gold claim about six miles up Tick Canyon there. They were doing more development work. As they trudged up and down the canyon to the Southern Pacific Railroad bringing in grub and supplies, Sheppard had noticed a white formation cutting across the country, about a mile below their claim. He proposed they drive a tunnel into this white formation and investigate. His partner demurred at first. It was only a brine deposit. But he finally acquiesced. They drove a tunnel a few feet (12 to 30 or 40) into the hillside and found some clear white crystals which they could not identify. The assayer in Los Angeles, to whom they took samples of the ore, said it was colemanite, a borate ore.

There was no one at the mine when Cahill and the agent reached there that morning in August. Cahill went into the tunnel. It was borate ore, all right. Pandermite(14) and colemanite. The streak at the mouth of the tunnel was about six inches thick, widening to some 12 or 14 inches at the end of the tunnel. On the hill above he could see the outcropping of a magnificent ledge, extending for about a thousand feet. Markers or monuments showed where several claims had been staked out on the outcrops. Cahill went on up the canyon to find the prospectors who had located the mine. As he feared, Blumenberg had beaten him to it. He had made arrangements to take over the property on a lease, paid a thousand dollars down to bind the bargain and told the prospectors he would start development work at once. He had even promised one prospector the job of foreman. In short, Blumenberg had it all tied up.

Cahill returned to Los Angeles and wired his report to Ryan at Ludlow. Ryan hurried to Lang. He learned where the agreement between Blumenberg (representing the American Borax Co.) and the prospectors had been recorded and obtained a copy of it. It was dated August 20, 1907, and was for ten years with the privilege of extension for another ten years and the same basis. The claims, which were recorded as lode locations, took in all the principal ledges, but there might still be a chance of P.C.B. acquiring some outside locations which had been overlooked. Johnny Mills(15) was put to work prospecting, ostensibly for himself. After two or three weeks though, he reported there was nothing left worth recording. P.C.B. had missed out altogether.

|

| Wash Cahill |

Blumenberg went to work at once, as he had promised. When Ryan went back again in December to see was going on, he found development work in progress. Also large notices posted in the vicinity of the mine warning people to keep off - Property of the American Borax Company.

There are several version of how Thomas Thorkildsen came into the picture at Lang. Thorkildsen’s own account makes him out as the original purchaser of the claims and winds up with a dramatic description of his forcing Blumenberg at the point of a pistol to remove the location notices and monuments which Blumenberg had sneaked in and put up on the property. Thorkildsen doesn’t explain, however, why he and Blumenberg became partners thereafter. The true facts are probably those given in Smith’s annual report for 1907. It seems that as early as January 5th of that year, a good eight months before Ebbinger and Sheppard drove their tunnel into the hillside, two prospectors of the names of Cook and Hopkins had located the property as placer claims. Ebbinger and Sheppard then came along that summer, found borax there, and located the ground as lode claims. It was these lode claims which Blumenberg had acquired.

Thorkildsen had tried to acquire these from Ebbinger and Sheppard, but was unsuccessful. Blumenberg’s development work was underway when Thorkildsen discovered what he and everyone else had overlooked – the original placer locations. He ascertained that they antedated the lode locations and promptly made a deal with Cook and Hopkins, paying them $2000 for their placer rights on the property and agreeing further to pay them sums amounting to $5000 annually, as long as he worked the claims. A short time later he amended his offer to an outright $15,000 purchase price of their claims.

The property now had two sets of owners – one holding the placer claims - the other the lode claims. Thorkildsen was now holding these placer claims over the American Borax Company (Blumenberg’s company) as a sort of club, reported Smith at the end of 1907. Thorkildsen brandished the club and made loud threats, but he didn’t take legal steps to oust the other faction from the property, nor did the American Borax Company appeal to the law. The fact was that neither side was to sure of its rights in the case, inasmuch as the courts at that time had not yet made it clear whether colemanite deposits should be located as lode or placer claims. Rather than running the risk of an unfavorable verdict, both parties ended up playing safe and saving faces. Half a loaf was better than none.

On January 15, 1908, the Sterling Borax Company was founded.(16) It consisted of the American Borax Company, the Frazier Borate Company (Stauffer), The Thomas Thorkildsen Company (Thorkildsen and Mather(17)), the Brighton Chemical Co.(18) of New Brighton, Pa., and the Stauffer Chemical Co.(19) of San Francisco.

|

| Thomas Thorkildsen |

The stock was owned as follows:

40% to American Borax Co.

20% to Thorkildsen

40% to Stauffer

Thorkildsen was elected president of the new company, with an office in Los Angeles. He was also general manager, in active charge of the mine. He had told Smith he’d show him. He was showing him.(20)

The great advantage for the Lang mine over all other borate mines which had been discovered up to that time was in location – only 40 miles from Los Angeles – and five miles from a branch of the Southern Pacific R.R. It meant cheap ore transportation – a freight rate of $6.00 a ton less than from the Lila C – and a plentiful labor market.

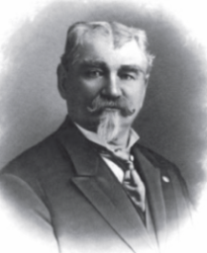

Thorkildsen developed the mine in two tunnels, one on each side of the canyon, a vertical shaft and an inclined shaft. Only the colemanite was used. The pandermite(14) they discarded. The crude ore was hauled by team to the S.P.R.R. and shipped to the Thorkildsen-Mather refinery in Chicago and the New Brighton refinery in Pennsylvania. Later, Thorkildsen built a small hand-rabbled reverberatory furnace(21) for calcining(22) the ore, which was then shipped as concentrate to the same refineries. At the same time, a substantial ore bin was built at the mine, and a 36” gauge railroad built from the mine to Lang Station, five miles away, to connect with the Southern Pacific. This railroad had to cross an area of the San Gabriel Forest Reserve(23), and to get permission to cross it, as also public domain, a special bill had opened through congress. After one unsuccessful attempt to do this, it was attached on a rider to a military appropriation bill and so was passed.

It was uphill from the station to the mine, with the grade becoming as steep as 7% in the big cut at the north end of the camp. Runaway trains were not infrequent, Roy Osborne recalls(24), particularly on rainy days, as the train descended with loaded ore cars from the mine. “Original railroad practice was to push the empty cars up hill ahead of the steam locomotive, but after one serious wreck and damage of the locomotive, this practice was reversed and the engine went ahead pulling the cars upgrade. The engineer was instructed that, if on the down trip the combined hand brakes of the engine and cars would not hold the train, he was to turn on steam and run into the cars and pull the pin on the slackened drawbar, and let the cars run wild down the canyon, and confine his attention to saving the locomotive.”

“There is a legend among the old railroaders of the camp that on the occasion of one runaway train on a rainy day, the engineer and the brakeman tried in vain to stop the train and when the brakeman jumped the engineer uncoupled the locomotive from the cars as per the Superintendent’s instructions, but still the engine kept slipping down hill at breakneck speed. Thereupon the engineer released the locomotive brake, set the reverse lever at the “go ahead” position to go upgrade, and opened the throttle. This expedient failed to diminish the downward speed of the locomotive; in fact, it decreased the traction of the wheels on the rails. As the locomotive careened around a particularly sharp curve the engineer jumped, leaving the setup in the cab as it was, oil fire burning under the boiler, brakes off, reverse lever set to go uphill, and the throttle halfway open. The locomotive slid down the canyon for a couple of miles, where, upon encountering a drier track and lessened grade, the wheels gained traction on the rails and the engine came puffing up the canyon and the engineer jumped on as it came past him, and rode on back to camp to summon help to look for the runaway cars, which were found in the ditch on a curve some three miles down the canyon. There is no record that the locomotive was blowing its whistle as it came puffing up the canyon unattended, but it is said that the bell was ringing. Could be, the track was rather rough.”

|

| Stephen Mather |

Roy Osborne doesn’t vouch for the veracity of this story. It probably happened before September 1910, when he went to work for the Sterling Borax Company as a surveyor. E.M. Stewart(25), a mining engineer, was Superintendent of the mine operations at that time. Prior to Stewart’s regime a Mr. Garringer, a practical miner and millman, was Superintendent.

Thorkildsen ran the job from the Los Angeles office and was a frequent visitor at the mine. Once in a great while, about every 3 or 4 years, he was accompanied by Steve Mather. Says Osborne recalling those visits “I was rather impressed by Mather’s quiet personality in comparison to Thorkildsen’s vivacious and even boisterous manner. Mather seemed always the gentleman, while Thorkildsen sometimes was not.”

The P.C.B. Co. kept a watchful eye on all activities at Lang. The agent at the railroad depot, for a consideration of $20 a week, forwarded regular reports as to shipments of ore. Clarence Rasor(26) drifted over there now and then to observe operations.

“The Sterling Borax Co. offers keen competition in borax and boric acid” wrote Smith to London in 1909. “Our reports are not complete, but we have learned from time to time that their ore is running 32 to 35% A.B.A.”(27) The information gleaned by P.C.B. included figures of employment (25 new in 1909), amount of ore hauled, amount of low-grade thrown out to be calcined(21) later, amount shipped, and destinations. The one point on which the company couldn’t seem to get the inside facts was operating cash.

In 1909 Thorkildsen bought out the American Borax Co. interest at Lang. The new setup was then as follows:

60% to Thorkildsen

40% to Stauffer

Thorkildsen had said he’d show Smith. He was showing him.(20)

“They operated,” said Smith, “as they would if there was no end to the ore in sight, but they may feel differently later. We sometimes think they are in hopes of irritating us into a frame of mind where we may be inclined to negotiate with them for their mines and plant and [????] generally.” Knowing his ex-employee as well as he did, it is quite probable that that was just what Thorkildsen was doing. In 1910, Smith reported that the production at Lang amounted to 12,660 tons, the ore running close to 40% A.B.A. The Lila C that same year took out __(28) tons, averaging __(28)% A.B.A. On a comparative basis, this meant that Lang was responsible for about 40% of the total U.S. output and the Lila C for the other 60%. The best grade of ore was taken out of the Lang mine first, but there was still plenty in sight. It was time, Smith decided, to make a deal with the Sterling Borax Co.

Nothing was announced around the camp but to the observant it was evident that something was brewing by reason of the frequency of Clarence Rasor’s visits. Even after the deal was consummated, few were aware of any change of ownership. The mine went right on being operated as before. Thorkildsen was still general manager. As far as Roy Osborne can recall – and he became Superintendent of the Lang mine when P.C.B. took over – Smith never visited the camp. John Ryan was there only once, in company with Mr. Zabriskie(29) and Mr. Baker.(30)

|

| Clarence Rasor |

The deal involved the purchase of P.C.B. of the entire capital stock of the Sterling Borax Company from its two stockholders – Stauffer Chemical Co. and Thorkildsen–Mather. The dates of these purchases were October 6, 1911, and December 1, 1911, respectively. P.C.B. then became the owner of the mine and roasting plant at Lang, and of the mining claims of the Frazier Borate Mine Co. in Ventura County. It was not until years later, however, that P.C.B. was able to disincorporate the Sterling Borax Company and absorb the mining properties into its own assets. The purchase price of the stock was $1,800,000, but the final cost, including interest and expenses, was considerable greater, creating a major increase in the company investment in the U.S.A. A down payment of over ½ million dollars in cash was made, and notes given to the various owners of the company for the deferred payments, which ran over a period of about five years.

In the meantime, the corporate structure of the Sterling Borax Company remained intact, with Thomas Thorkildsen as president. Mr. Bertin A Weyle, attorney for P.C.B., was made secretary, and Clarence Rasor was placed on the board of directors. The corporate books were kept in Thorkildsen’s office in L.A. The accounting work was in charge of a firm of accountants in L.A. – Palethorpe, Probert and McBride. They cooperated quite satisfactorily, and in time P.C.B. was able to direct the accounting methods and reports to conform with its own ideas.

At the time of the sale of the stock to P.C.B., the Sterling Borax Co. had a contract to export 2000 tons of colemanite annually to Thomas Henderson, a refiner in Glasgow.(31) Their obligation P.C.B. assumed for a limited time. It was then taken over by Borax Consolidated, Ltd.(32), who made deliveries from other sources of supply then the U.S.A. The P.C.B. Co. also took over a contract which the Sterling Borax Co. had with the Thorkildsen-Mather Co. of which they guaranteed to supply the T-M refineries at New Brighton, Pa., and Chicago, with borate ore in concentrates (40% B2O3), up to 650 tons a month for a period of ten years. Thorkildsen-Mather retained the right to sell their borax and boric acid output at any price they chose.

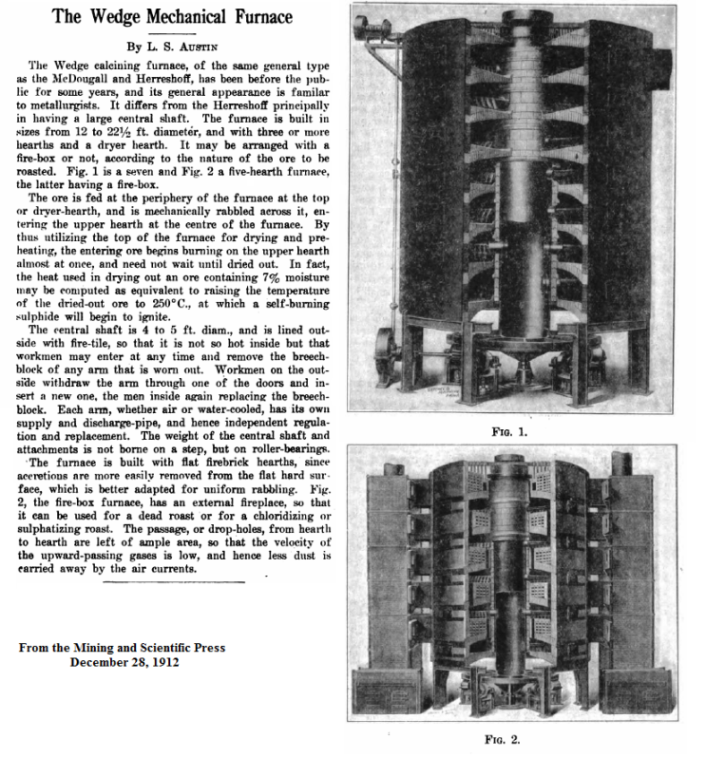

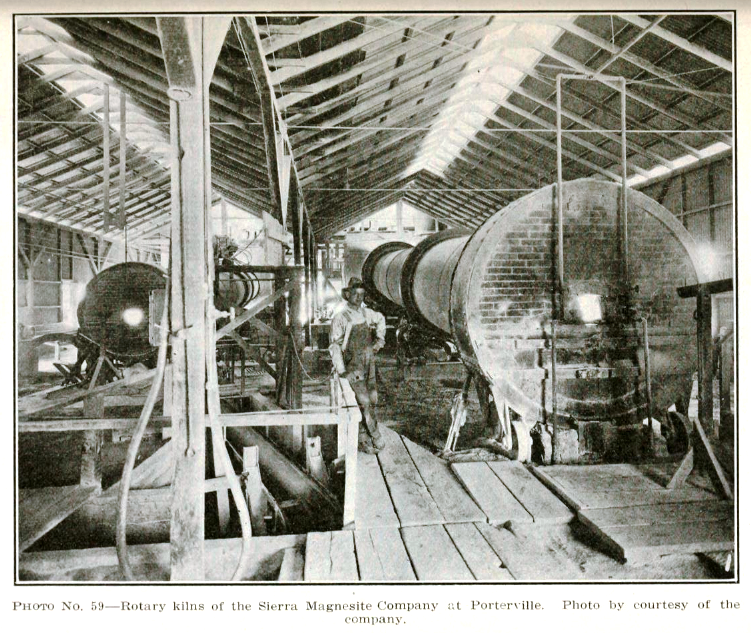

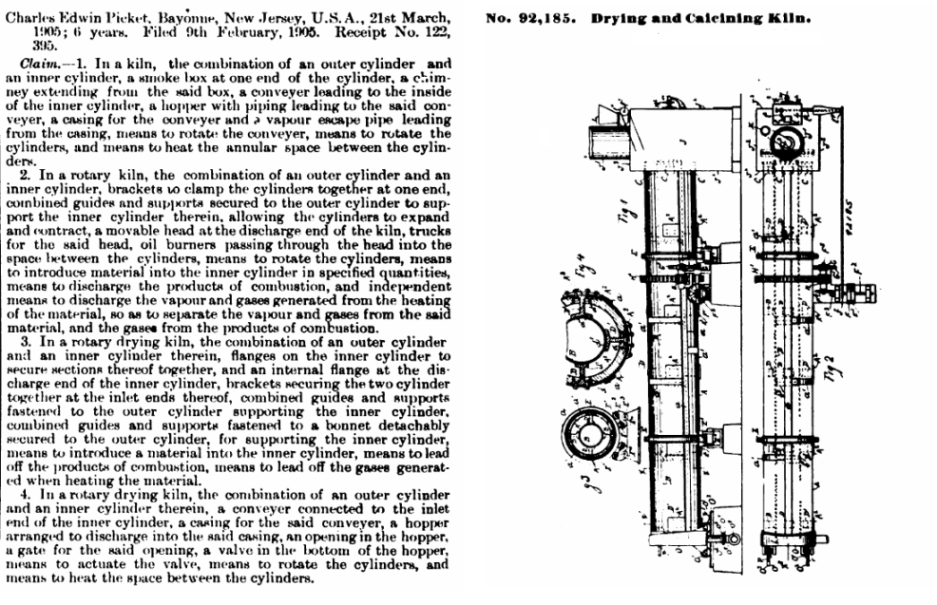

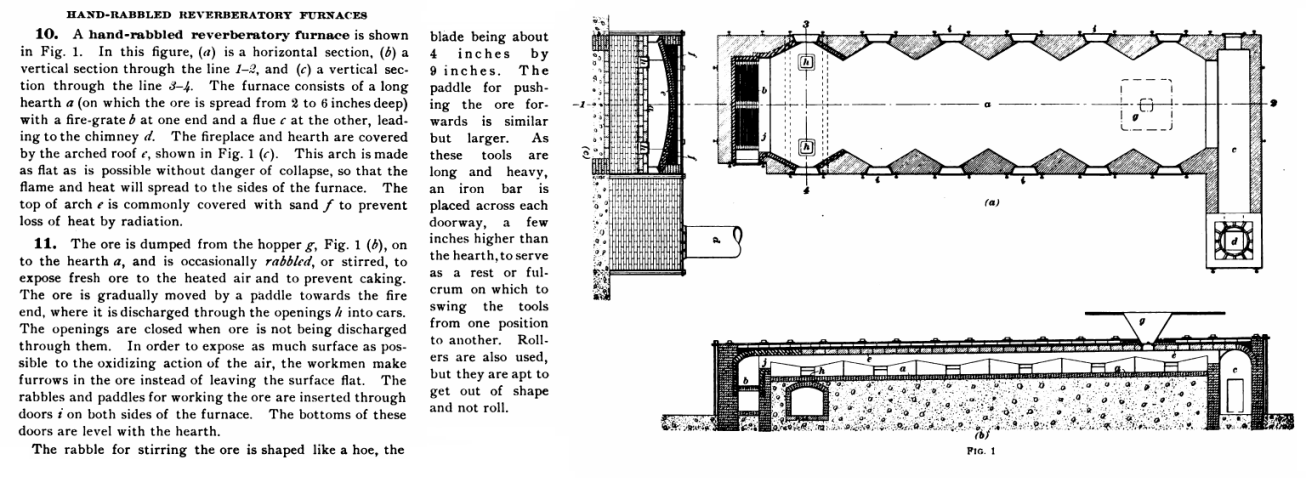

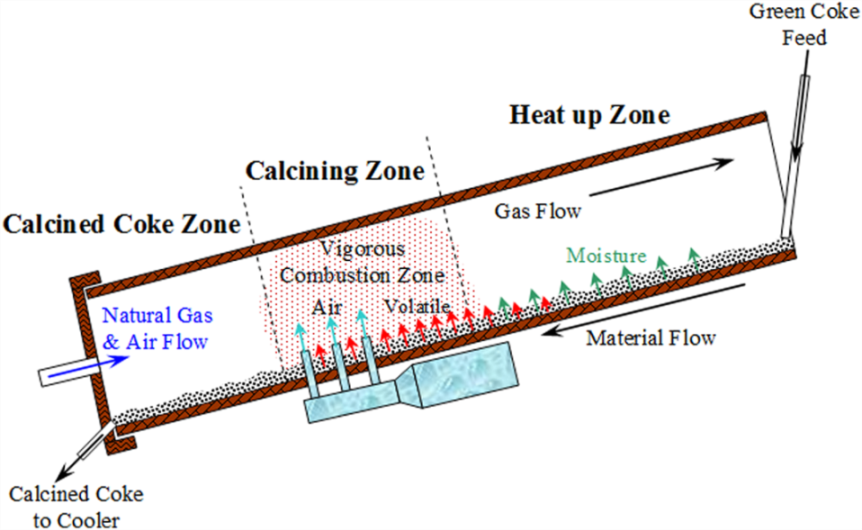

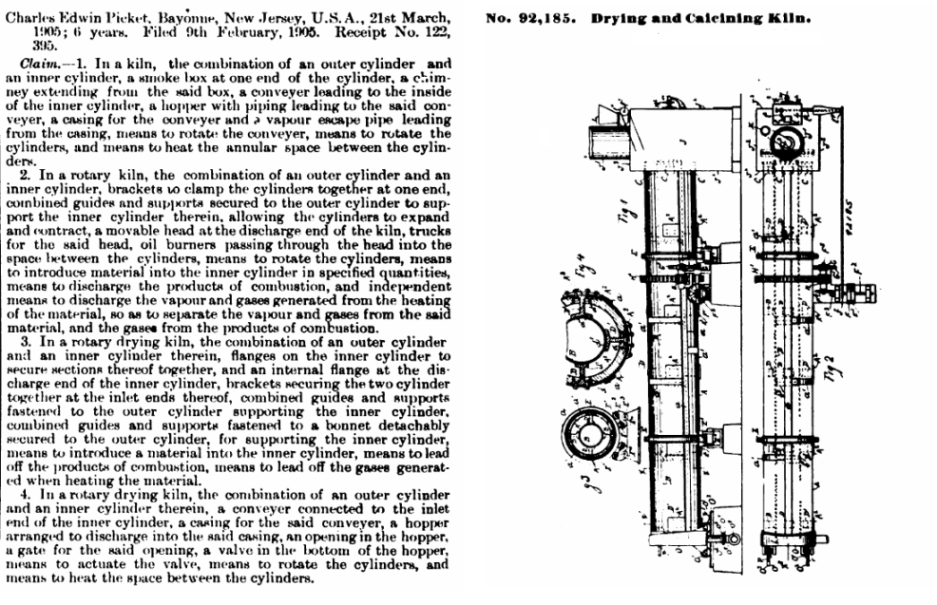

With the added backing of the P.C.B. Co., the Sterling Borax Co., about 1913, brought in electric power from the Southern California Edison Co. in Mint Canyon. The mill was modernized, two wedge calcining furnaces(33) installed, and an electric house provided for the mine, all of which helped to increase production. In 1914-1915, the again increased production sinking a new vertical shaft and installing two Pickett rotary calcining kilns.(34)

The number of men employed at Lang varied. Sometimes there were as few as 16 on the payroll, at the peak probably 100. During the early years Lang was a “stag” camp. The only diversions were poker and cribbage games, hunting trips for deer and quail in season within two miles of camp, and occasional trips to Los Angeles. “And then in 1913-1914”, says Roy Osborne, “some of us were able to afford automobiles; the top brass first, and in the succeeding years even the lowliest mucker(35) came rustling a job in his Model T Ford.” Roads were not what they are today, but even then a man could get home from Lang in an hour and a half. Truly a suburban mine!

|

| Christian Zabriskie |

With the advent of automobile transportation and electric power, it followed that the married employees would want to bring their wives to camp, so the company built a few modest cabins for the staff members and allotted land for other employees who cared to build their own cabin for their families. There was a limit to the number however, because of the water shortage. A small amount of water was caught in the floor of the canyon above the mine, from a little stream which flowed through there, and was piped to a tank in camp, as was the water brought from an assessment tunnel half a mile east of the mine. But there was not enough to supply the needs of the camp. The main supply was hauled in tank cars from the Southern Pacific tank at Lang Station. Because of the steep grades on the railroad and the small locomotive, this supple was necessarily limited.

With the coming of families in the camp, a school(36) meant the inevitable school house dances and card parties and romances. This marked the transition from a frontier camp to a more or less modern camp. In those days – “It was always a good camp,” declares Roy Osborne, and others who lived and worked there echoed his sentiments, “no strife, and a fine spirit prevailed between the employees and their families and the company staff.”

Between the two companies in dual control of Lang, affairs, in general, were smooth enough, but occasionally there were clashes with the tempestuous president of the Sterling Borax Co. over questions of policy. What attitude Thorkildsen would take on any matter was always unpredictable. In the end, of course, he was subject to the orders of the P.C.B Co. but he could be counted upon to put up a determined fight if he felt they conflicted with his own view. More then once, Mr. Zabriskie was called upon to step in and straighten things out with Thorkildsen.

The last time was in 1920. For nine years the P.C.B. Co. had been maintaining the Sterling Borax Co. as a separate corporation. Now it decided to be rid of the trouble and expenses of such an arrangement and disincorporated the Sterling Co. From London came orders to go ahead and wind up the company’s affairs. In order to do this it was necessary to get Thorkildsen’s signature, as president and director of the company, on the resolution to disincorporate, as well as on the deeds and other legal documents. Mr. Zabriskie informed Thorkildsen of the plan. Before agreeing, Thorkildsen wanted to know how this would affect the Thorkildsen-Mather ore contract which still had a year to run. Mr. Zabriskie assured him that the B.C. Ltd. would guarantee fulfillment of the unexpired part of the contract, and that Thorkildsen would be furnished with such guarantee in writing. Thorkildsen also wanted to know “how about an extension of the contract after it expires?” In answer to this, Zabriskie told him that it was the intent of P.C.B. to give him a new contract when the present one expired, but that it was too early to discuss prices and terms. This appeared to satisfy Thorkildsen and Mr. Zabriskie assumed the matter was settled and they could count upon his cooperation in the dissolution proceedings.

Instructions were given to P.C.B.’s attorney Mr. William Thomas of San Francisco to draw up the necessary papers. While they were being prepared, rumors began to float about that he had changed his mind. He wasn’t going to play ball after all. Perhaps there was no foundation to such rumors, but Mr. Thomas decided to take no chances. It would be awkward, to say least, to have Thorkildsen balk at the last minute and refuse to sign the papers. Better have a preliminary meeting of the parties concerned and make sure that everything was quite clear. Mr. Zabriskie was 3000 miles away in New York and could ill afford to take the time to come to San Francisco. However, he agreed to make the trip rather than have any hitch in the proceedings.

|

| Richard Baker |

The meeting took place in the office of Mr. Thomas and was attended by Mr. Thomas, Mr. Zabriskie, Mr. Thorkildsen, Mr. Mather, Mr. Bertin Weyle, and Mr. Dudley. “Mr. Thorkildsen was wordy and aloof,” Charlie Dudley recalls. “Mr. Thomas stated the purposes of the meeting and explained the advantages and necessity of disincorporation. As Thomas had anticipated, Thorkildsen began to demur, and it was up to C.B.Z.(29) to do his stuff. Before this had gotten very far, C.B.Z. walked over to him and said, “Tom, lets you and I go out and talk this matter over together.” Thorkildsen agreed, and they went into another room, accompanied, I believe, by Mr. Mather.”

“They were gone about ten minutes and when they came back, Thorkildsen, without any preliminaries or explanations, said “Ok – let’s play ball.” Instantly the tension relaxed and everybody felt better. Thorkildsen signed the papers which the lawyer had prepared and we all accepted Mr. Thomas’s invitation to accompany him to the Universal Club where he had stored some choice liquid refreshments of pre-war vintage (pre-World War I, that is. This was during the Prohibition Era). Mr. Zabriskie did not tell us what he said to Thorkildsen during their private talks, but it’s a safe bet that he did not mince matters. He had assured Mr. Baker that the disincorporation would be carried out promptly and he was going to make good.” Mr. Zabriskie, like Thorkildsen, was a bon vivant and entertaining social companion, but in discussion he could be tough.

After disincorporation, the Lang mine was operated on P.C.B. property, with Mr. Osborne as Superintendent in charge. The mine was to this time becoming worked out, and production costs were rising, and in January, 1922, the company decided to suspend operations. Some crude ore was mined and shipped in 1923, but the mill did not operate again. It was dismantled that same year and sent to Death Valley Junction. Part of the mine equipment went to Ryan. In 1925 the railroad was torn up and disposed of. The camp of Lang was beginning to disappear from the map.

During 1923 and again in 1925 efforts were made to dispose of the mine hoist in the mining region of Southern California. There was no sale for it and it remained in storage in Wilmington until 1927 when use was found for it on the main production shaft at the new discovery in the Kramer area.

When the P.C.B. Co. leaves a place, it leaves little behind. At Lang today there are the remains of the cement foundation and in the hills the engine hoist once stood and farther up the canyon beyond the camp the remains of the mill foundation. Nothing else, unless you count the dumps of bluish shale, several hundred feet in depth, which testify to the work once done there. The hills around about are silent.

[End of Chapter]

Chapter credit:

Pacific Coast Borax Company, Chapter XII: The Sterling Borax Company-Lang, Ruth Cornwall Woodman Papers, Box 1, Folder 26, Special Collections & University Archives, University of Oregon Libraries, Eugene, Oregon.

Sources used by Ruth Goodman (and these are not all inclusive):

Memorandum by John Ryan to William L. Locke, July 2, 1914.

Letter to Ruth Goodman from LeRoy Osborne (Superintendent of Sterling Borax Co.), March 30, 1949. (PDF)

Letter to Ruth Goodman from Norman Ross (master mechanic for SBC), April 10,1949. (PDF)

Account by W.W. Cahill, February 19, 1947. (PDF )

Account by Charles R. Dudley. (PDF )

"A Flurry in Borax", Chapter from Happenings: A Series of Sketches of the Great California Out-Of-Doors, by W.P. Bartlett, Porterville, California, 1927, pp. 22-28. (PDF )

Ruth Goodman's summary of her trip to Sterling Borax Mine in 1947. (PDF)

The two letters are from the Special Collections & University Archives, University of Oregon Libraries. The Ryan memo, the Cahill and Dudley accounts, and Ruth Goodman's trip account are from the U.S. Borax Archives at the National Park Service in Death Valley National Park.

Notes

(1) Francis Marion “Borax” Smith, a.k.a. the “Borax King” (1846-1931), was the president of the Pacific Coast Borax Company (PCB), which he formed in 1890. In 1899, Borax Consolidated, Ltd., was formed by Smith and a group of British investors with headquarters in London, England. They assumed ownership of PCB. The annual report that Goodman was talking about was probably a report that Smith wrote to Borax Consolidated in late 1907 or early 1908 for the year 1907. (Photo from his 1917 U.S. passport application.)

(2) Henry Blumenberg, Jr. (1876-1934) was manager of the American Borax Company. In his lifetime, he was issued over 30 patents covering various chemical processes, such as a patent for "the process of making boric acid and sodium borate". Blumenberg is described as "a womanizing borax-mining magnate" in the book Unreal Estate, by Michael Gross, Broadway Books, New York, 2011, p. 88. More Blumenberg comments here. (Poor photo from the Los Angeles Herald of June 29, 1912.)

(3) The Calm brothers were the company M. Calm & Bro. They were Maxmilian (the senior partner), Edward, and Charles. They had one patented claim and 10 unpatented claims in Ventura County, Ca. The claims were located in 1899 and operated continuously from 1902 to 1907. They were sold in 1912 to the National Borax Company.

(4) Thomas Thorkildsen (1870 - 1950). Both parents were born in Norway, but he was born in Wisconsin. Thorkildsen once worked for the Pacific Coast Borax Company under Smith, but was fired in 1898. In 1899, he and John Stauffer formed the Frazier Borite Company. In 1904, Thorkildsen and Stephen Mather, another former employee of Smith, would start the Thomas Thorkildsen & Co., which would become the Thorkildsen-Mather Borax Company in 1907. Thanks to the Sterling Borax Company, both would become a millionaires and Thorkildsen would become the new "Borax King." (Photo from his 1919 U.S. passport application.)

(5) The Stevens Group of mines were near Calico in San Bernardino County, Ca. These deposits of borax were discovered by Calico storekeeper Hugh Stevens in 1882-1883. In 1888 they were sold to Borax Smith.

(6) The Frazier borax ore district was located in the extreme northeast corner of Ventura County, Ca., in the vicinity of Frazier Mountain. Borax ore (colemanite) was discovered there in 1898 and produced almost continuously from 1899 to 1907.

(7) The Lila C mine was named by its owner William Coleman for his daughter, Lila (who died at the age of 6). It is located in Inyo County in California near the border with Nevada at the outer reaches of Death Valley. In 1890 Coleman's finances collapsed allowing Smith to obtain possession of the mine from the creditors. Smith then incorporated it, and other properties, into the Pacific Coast Borax Company with him as president.

(8) William Washington “Wash” Cahill (1873-1959) was an employee of Pacific Coast Borax Co. He was the superintendent of the Tonopah and Tidewater Railroad in Death Valley. He became the historian for the Death Valley Days radio and TV show and helped Ruth Woodman while she was writing her history of the Pacific Coast Borax Company, including this chapter on the Sterling Borax Company. (Photo from 50 Years in Death Valley by Harry Gower, Island Printing & Engraving Co., San Bernardino, Ca., 1969.)

(9)John (Jack) F. Duane (1854-1913) was a commission merchant (someone who buys or sells products for a percentage of the sales price) dealing with mining supplies and coal. He had a close relationship with PCB.

(10)The Tonopah & Tidewater Railroad was constructed and owned by Borax Smith. It was the line that the Pacific Coast Borax Company used to take refined ore from Death Valley to Ludlow,California, where it was transferred to the Union Pacific Railroad.

|

| Lewis Ebinger |

(11) Louis Ebbinger (1844-1925) – Incorrect spelling. In his biography, it is spelled as Lewis Ebinger. In Ancestry.com the records show Lewis Ebinger. (Photo from A History of California and an Extended History of Los Angeles and Environs, 1915.)

(12) John Ryan (1849-1918) was general manager of the Pacific Coast Borax Company. The town of Ryan in Inyo County, California, is named after him.

(13) Henry Sheppard - I have found no information on him except that his name was probably spelled Shepherd. A gold mine in upper Tick Canyon was once named Shepherd and he mined for gold there. On the 1910 US Census, there is a 55 year old gold miner living in Arizona named Henry C. Shepherd, but it is impossible to tell if that is the same man.

(14) The term pandermite was incorrectly used in California to designate howlite. Pandermite is really another name for priceite, another borate mineral sometimes found in Tick Canyon. Howlite is still very common in the dumps of the Sterling Borax mine.

(15) John J. (Johnny) Mills (1865-1948) was a prospector who first came to Death Valley in 1896. He would became an employee of Pacific Coast Borax Company and would eventually work at the Furnace Creek Inn, which was built by the PCB in 1926.

(16)Woodman says that the company was founded on January 15, 1908. That is probably when all parties agreed to form a new company. The State of Nevada Biennial Report for the Two Years Ending December 31, 1908, reports that the incorporation was filed on February 17, 1908. The California State Library News Notes for January-October 1909, for the Fourth Quarter 1908, reports the incorporation was on October 12, 1908.

(17)Stephen T. Mather (1867-1930) was a one-time employee of the Pacific Coast Borax Company. At PCB Co., he became friends with Thomas Thorkildsen, another employee. For PCB, Mather had the idea of adding "20 Mule Team Borax" to the company's box. After leaving PCB in 1903, Mather and Thorkildsen organized Thomas Thorkildsen & Co. in Pennsylvania in 1904. In 1907, it was renamed the Thorkildsen-Mather Company. Mather bought out Thorkildsen in 1923 and changed the name to the Sterling Borax Company. When Mather died in 1930, that company passed on to Mather's heirs. There is mention of it many times after 1930. As late as 1970, the Sterling Borax Company was listed in the Thomas Grocery Register. Both men became millionaires by 1914. Mather would become the first director of the National Parks Service in 1917.

(18) The Brighton Chemical Co. of New Brighton, Pa. was a branch of the American Borax Company. The plant produced borax and boric acid.

(19) The Stauffer Chemical Co. of San Francisco was founded in 1886 by John Stauffer and Christian de Guigne. According to the Pasadena Independent Star-News of February 16, 1958, colemanite (a form of borax) was discovered in Lockwood Valley in 1899 and would eventually be sold to John Stauffer and Tom Thorkildsen. They formed the Frazier Borite Company. Stauffer and Thorkildsen became business partners at that time and is probably why Stauffer became a part owner of the Sterling Borax Company.

(20) Thorkildsen had worked for "Borax" Smith since about 1889, but in 1898 he was fired. On his way out he threatened to start his own borax company. Smith responded with his own threat to bury Thorkildsen if he did. Woodman used this phrase twice. She probably would have removed one of them in her final version of the chapter.

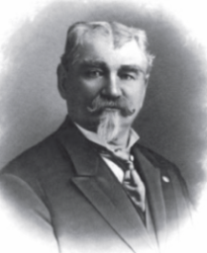

(21) Hand-rabbled reverberatory furnace - furnace where the fuel is not in direct contact with the ore but heats it by a flame blown over it from another chamber. See below for a diagram that includes an explanation.

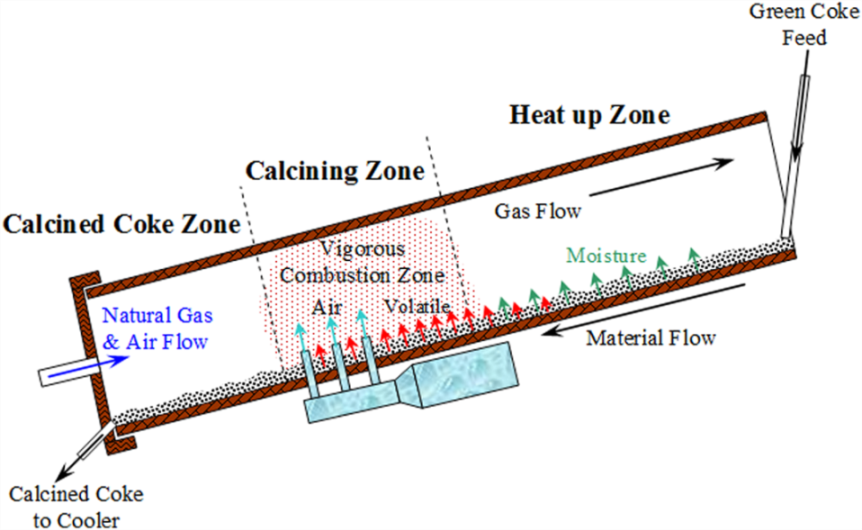

(22) Technically, calcination is the process of heating a material to cause chemical dissociation (separation). For borax, calcining heats the ore driving out most of the water, disintegrates the colemanite, and causes what's left to gather into easily separated lumps. A furnace (also called a kiln or calciner) does the heating.

(23) The San Gabriel Forest Reserve was established by the General Land Office in California on December 20, 1892. It became a National Forest on March 4, 1907. On July 1, 1908, the San Gabriel was combined with the San Bernardino and Santa Barbara Forest Reserves to create the new Angeles National Forest, the first National Forest in the state.

(24) In a personal letter to Ruth Woodman included here.

(25) Edgar M. Stewart (1883-1920) was killed in an automobile accident on a mountain road near Lang on April 6, 1920. He was Superintendent for ten years.

(26) Clarence M. Rasor (1873-1946) was a field engineer for the Pacific Coast Borax Company. (Photo from his 1920 U.S. passport application.)

(27) The value of borax is fixed in accordance with the percentage of anhydrous boric acid (A.B.A.) in the ore. The higher the percentage, the more valuable the ore.

(28) These two numbers are missing in the manuscript.

(29) Christian B. Zabriskie (1864-1936) was the vice-president of Pacific Coast Borax Company. Zabriskie Point in Death Valley was named for him. Photo from the interpretive sign at the Zabriskie Point site in Death Valley National Park.

(30) Richard C. Baker (1858-1937) became Smith’s British business partner at Borax Consolidated, Ltd, in 1899. He would later became the president of Pacific Coast Borax Company in 1913, when Smith went bankrupt, and would remain president until he died in 1937. Baker, California, was named for him. The mineral Bakerite was also named for him. (Photo from the internet.)

(31) In Scotland.

(32) Headquarters in London, England.

(33) Wedge calcining furnace - a type of furnice or kiln. See below for a description and photo.

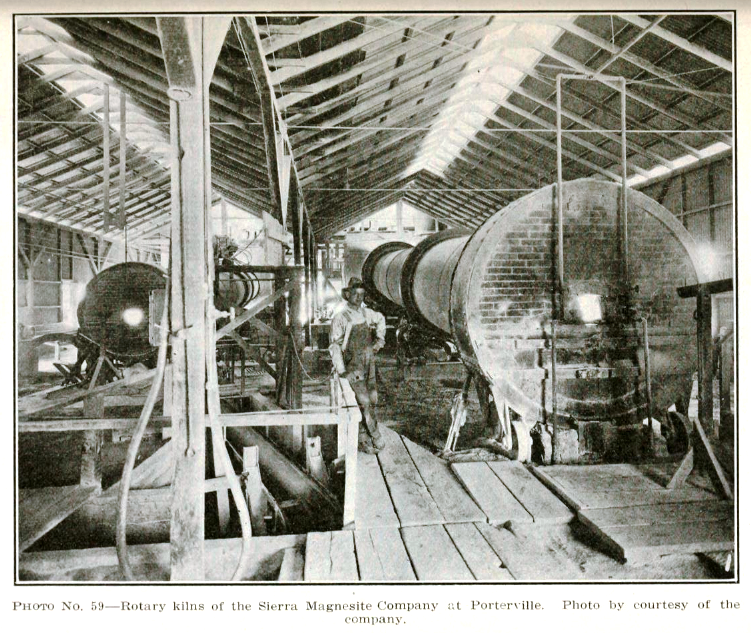

(34) Pickett rotary calcining kiln - a rotary kiln is another type of furnace, except using an inner and outer horizontal tubes. In 1905, Charles Picket patented an improved one. See below.

(35) A mucker is a person who removes muck (waste, debris, broken rock, etc.), especially from a mine, construction site, or stable.

(36) According to Roy Osborne, the school was built on a hill overlooking the camp.

From the International Library of Technology, Surface Arrangements - Roasting and Calcining Ores, 1902

Wedge furnace.

Diagram of a rotary kiln. Substitute "borax ore" for "coke".

Photo of rotary kilns from Magnesite in California by William W. Bradley, California State Mining Bureau, Bulletin No. 79, 1925, p. 131.

Picket's Patent for a rotary kiln. (From the Canadian Patent Office Record of March 1905.)

Ruth Cornwall Woodman with unidentified man (may be Wash Cahill). Photo credit: Catalog Number PEO 033A, U.S Borax Collection, Death Valley National Park, National Park Service