Ben Truax got to talking loose the other day. He was up in his cabin in Agua Dulce optimistically watering a few trees.

He was talking about a prospector, named Shepherd, who maybe graduated from the mining prospects of the 1890’s, up around Acton, after they had pooped out. Sticking to the traditions of Old Soledad, Shepherd kept poking around its tributary canyons, and the ridges intervening.

One thing Shepherd found – whether he really expected to or not – (it’s seldom that the expected happens to a prospector) was a spring of sweet water up in the hills back of Escondido Canyon. That is what it is called now. Maybe this gave him a toe-hold, so to speak, to more or less fine-tooth comb around the place.

You see, Shepherd already had a grubstaker, whatever his name was, who had a Saloon down on Eleventh and Main Streets in Los Angeles.

Who could ask for more than a grub stake and a spring in a nice, quiet lost area – and believe you me, it had been largely lost since the Soledad mining boom and camp had busticated at the end of the 1860’s.

In all this peace and quiet, the story goes, Shepherd actually found a gold pocket that produced some $2,200 about 1906. This was fine, and the co-owners in this enterprise tried to find some more, while at the same time what they already had was dwindling. Then the saloon man took what was left of his share and oozed out of the picture.

This left Shepherd having nothing else to do – and a spring of water to do it by, and to somehow keep on prospecting in lonely splendor.

Back in those days, the Los Angeles Examiner had available service possibly long forgotten. If a mineral specimen could be produced, the Examiner service would tell you whether it had commercial value or not.

With gold ore samples in short supply, Shepherd took to sending in the other specimens native to the region, but was always assured that they were of no commercial value. In fact he had so many assurances to this effect that it grew monotonous and he broke down and sent some samples in to an that the specimens represented [sic].

The assayer reported back that the specimens represented commercial value, not for gold, but for borax. The specimens submitted by Shepherd were a reasonable grade of Colemanite which at the time was in short supply.

This put a whole new light on Shepherd’s activities. It gave talking points or verbal ammunition, so to speak. He sold his mining claims to a Los Angeles mining operator, Tom Thorkildsen, for promotion development and profit, sometimes around 1908.

This leads to the story of Sterling, a Ghost Camp, once claiming the biggest payroll in old Soledad township – and having it too. Today the easy way to get there is right over Davenport road, off Mint Canyon.

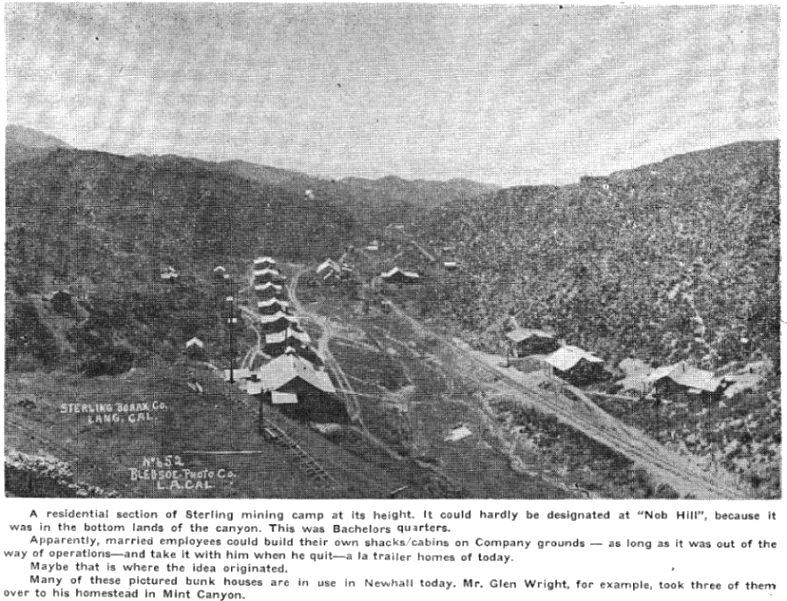

The story of the Sterling operation goes back, in turn, to the folks that knew the Camp some 50 years ago – folks like the Glen Wrights, and Walter Baughers, the Murphy family who displaced the Indians almost a century ago and the Henry Hendly family were all part of the Sterling story. They have been most generous with old pictures, and old stories, and this article is only a composite of what they have related.

To get back to our story – Thorkildsen experienced quite a lot of problems. For instance, it was six miles down Tick canyon to Lang, the nearest railroad point, and at the time was the only way out of the Sterling site. Davenport road, as it is know today was decades in the future. As a matter of fact, Sterling’s superintendent, a gentleman named Stewart or possibly another named Osborne, broke trail for that last road, so Sterling employees could get over from Mint Canyon country, in the early ‘teen years.

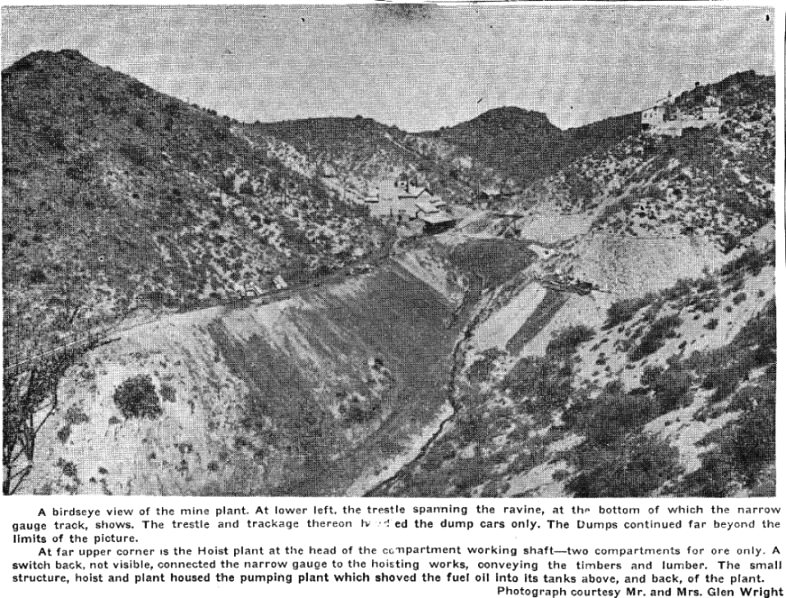

The ore ran about 10 percent borax. The nearest refineries at that date were in Chicago and Pittsburg, and the freight charges to those places were exorbitant considering the 90 percent waste. During World War I, shipments were made from Lang to Bordeaux. Pacific Coast Borax had a Wilmington refinery in the late ‘teens, but Thorkildsen could not wait for that to be built.

Labor costs were high. The deposit had to be mined which meant a tri-compartment shaft. “Soft formation” meaning that the roof might come down on your head, or the tunnel sides press in and slough with or without provocation. This upsets a miner when he feels the ceiling is about to drop on his head. The situation called for timbering on quite a scale, with 10x10 mine braces lagged into place at 5 foot centers.

The ore body would then be mined on three levels, 100, 200 and 250 feet. The shaft went 50 feet farther, bottoming for the drainage pumps. To handle the tonnage called for a rather stout hoist, and an expensive one too.

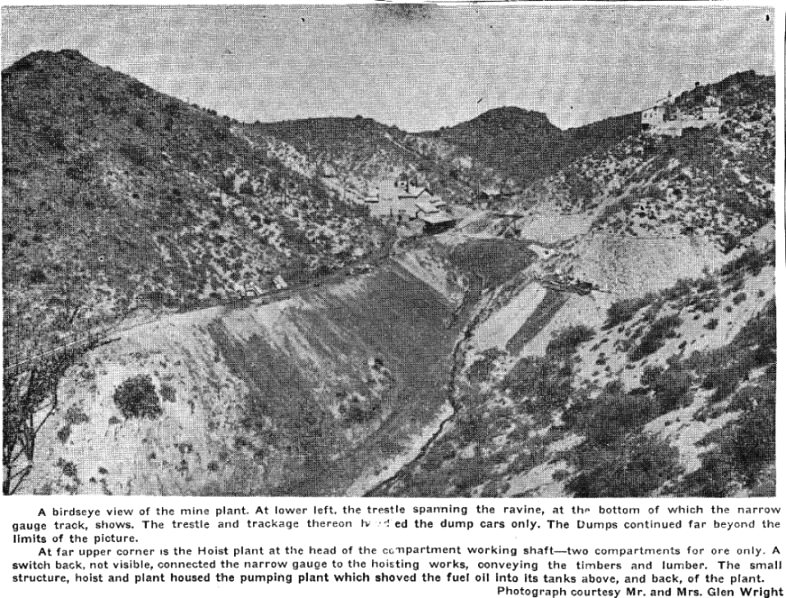

The heavy percentage of waste, made a reduction plant a must, unless the railroad was to get all the profits. The canyon was so narrow and steep sided it was impossible to get the head frame and hoisting works on the same side of the canyon as the plant. The plant was then built on the other side of the canyon.

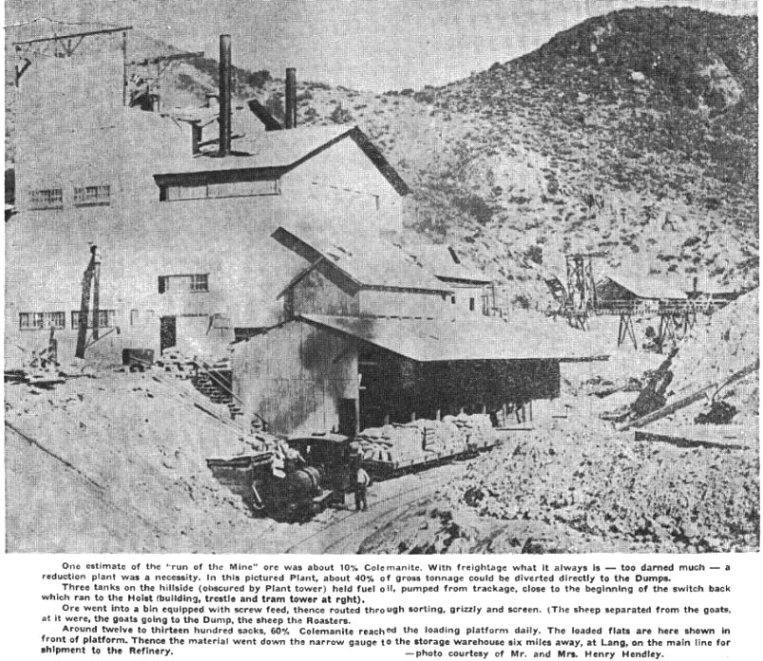

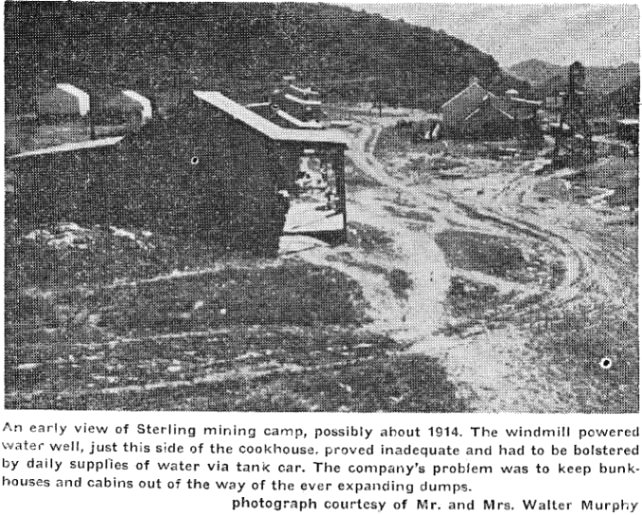

All this work called for much labor, which had to be fed and cared for. Having no choice, the newly formed Sterling Borax Company expanded their plans to include housing, meaning a commissary and bunk houses for the bachelors, and cabins for the married men with families. Cook houses had to be good – or you just could not hold the men.

Being purely a company group, no stores were involved. Married folks could get their supplies through Bercaw’s store at Saugus Junction. It took all day to get to Saugus and back and this popularized monthly orders at Cohn’s down in Los Angeles.

With a payroll of 160 men, there were already more folks than could be watered. That meant a tank car and whenever the train made Lang, two, and sometimes three, times daily, the tank car could be filled to bolster the Camp supply.

The first locomotive was almost too small. It had to stretch to handle three loaded flat cars. So they got a bigger one, oil fueled, steam powered, that raised the load two flats to five. Of course, on such a long, steady down grade, it sometimes ran away – and occasionally it might jumy [sic], down by an unavoidable S curve. Ben Truax herded the locomotive for nearly ten years. Clarence Gerberick and Glen Wright also spent time at the throttle.

The return load, for the long pull, was mainly water and timbers. The mine ate timbers like they were chocolates. In fact, the timbering cost ultimately proved to be a main factor in closing the mine. You practically had to press the working faces for safety. The pressures on the timbers were terrific.

Wright swears a 10x10 turned into a 6x16 in a fortnight.

In 1917, the State Mining Bureau reported a Los Angeles County Borax production of nearly a half million, in dollars, “chiefly the output of the Sterling Borax Company … the corporation controls some 1,200 acres and mines a large deposit of colemanite … the crude material is separated from such impurities as clay and shale, and calcium, and the borate is shipped to Pittsburg and Chicago to be refined into commercial borax.”

In 1923, the Bureau reported the deposit “occurred as thin and thick seams, almost vertical, and has considerable howlite associated with it.”

No, I don’t know what Howlite is either – unless it was a noise emanating from the Company’s stockholders. Oh, never mind.

The dumps grew from an ash heap into a mountain. At first, the mine cars could be pushed off the shaft platform by hand, sort of a substitute mule arrangement, but, as said, the canyon was narrow, and the dumps stretched longer and longer. It took too long for one man’s round trip, so a Fordson [tractor] sort of spread the waste for awhile until this was also outmoded, and a gasoline propelled mine locomotive on a 24 inch gauge mine track, took over the job.

Mine operation was simple. The ore came up one of the two freight compartments the shaft. The third compartment was for the men. By changing methods, chuting, conveying belt, latterly by bucket on an aerial tram, the ore reached its bin at the plant. It was sorted, screened, grizzled, as necessary, and parted company with about 40% of itself, which diverted to the waste dump cars.

The remainder hit hand roasters in its early operations, later the wedge roasters (greater capacity) in 1915. The roasters were heated by oil furnaces. The roasted dehydrated ores, practically disintegrated, were sacked and piled on the loading platform waiting for the first narrow gauge freight headed out for the Lang warehouse, on the standard gauge main line.

The buyers lacked sentimental interest in canyons of the San Gabriel.

They wanted a profitable operation. Who could blame them?

The new owners set picket roasters, a considerable improvement reflected in costs.

Still the mining cost too much. Timbering called for at least a set a day in operating face. It took eight hours to lag a set in place.

The faces were broken on a six hole pattern, holes drilled, two each, top, bottom, and middle. The plant worked two shifts in the mine, and three shifts on the roasters, for a daily tonnage of about 180 tons.

Other borax sources had been found, workable by open pit, drag line, or scrapers. By 1922, Pacific Coast Borax Co. was discouraged. Abandonment, and demolition took until 1923. There was nothing left but a few massive concrete abutments of old foundations for plant and hoist – and a changed landscape. Nothing could be done about that.

The Borax operation had been very good for the township. The 160 man payroll was far and away the biggest in the area. Sterling worked more folks then the rest of the township put together.

Peculiarly, not many Newhall boys worked in the Borax operation. Pico oil was their idea of a good job, if you could get on. This, however, was a lot smaller operation.

Glen Wright bought three units, which he used on his Mint Canyon homestead.

Although service in World War I had interrupted the pay checks of a surprising number ...